When most Marylanders hear about transportation and development, they think of the flashy, billion-dollar projects—the Purple Line, the ever-delayed Red Line, or the latest widening scheme for I-495. But while the headlines focus elsewhere, a quieter and arguably more consequential transformation is unfolding along the 35-mile stretch of I-270 between Bethesda and Frederick.

This “quiet transformation” isn’t being driven by one giant project or a new superhighway, but rather by a series of incremental zoning reforms, mixed-use developments, and industry migrations that are steadily reshaping the character of Montgomery and Frederick Counties. And like most government-engineered “transformations,” it’s producing winners and losers—raising serious questions about housing affordability, traffic, taxes, and the future identity of these communities.

From Empty Office Parks to “Live-Work-Play” Utopias

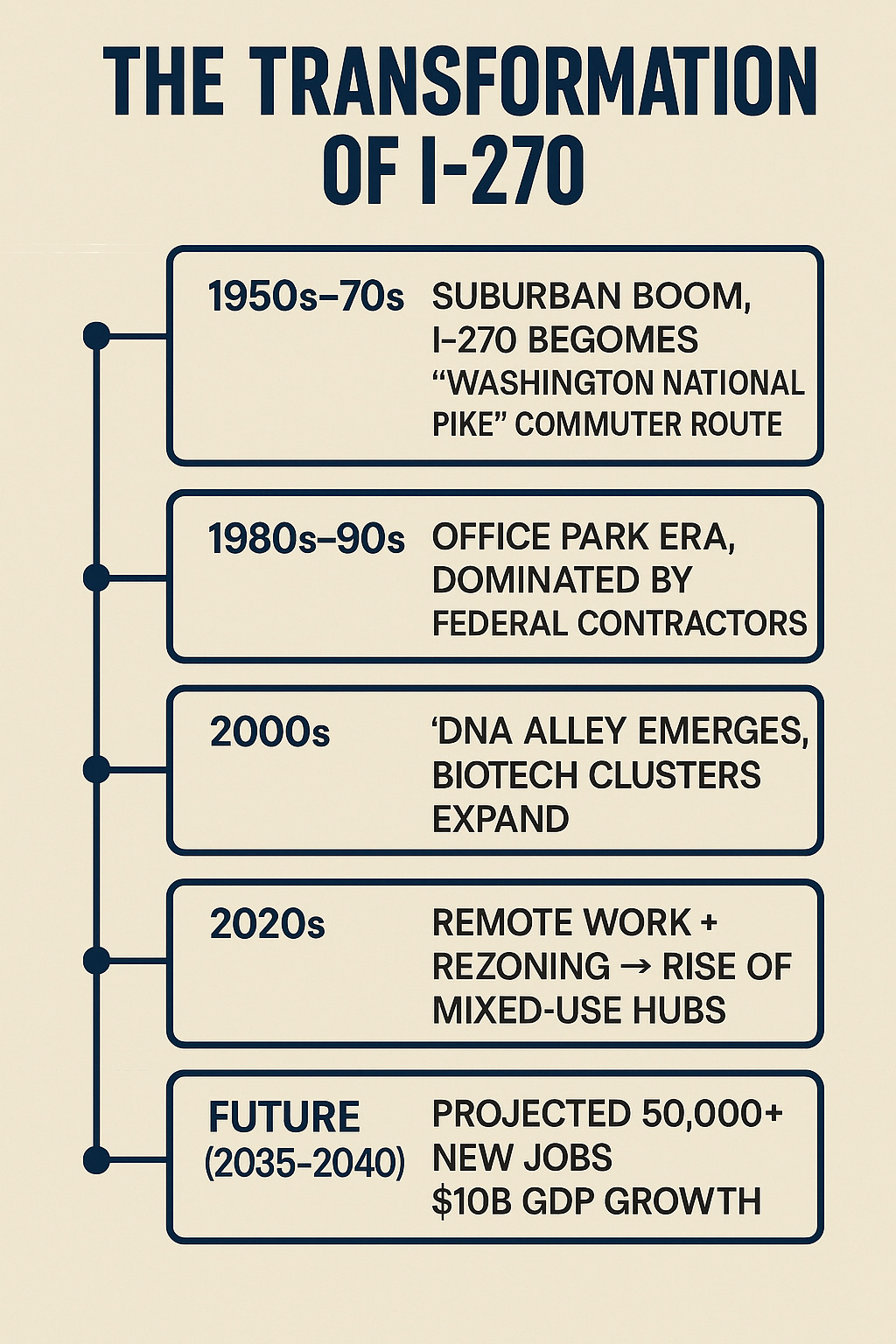

Once upon a time, I-270 was the land of sprawling suburban office parks: acres of glass buildings surrounded by seas of asphalt, populated by federal contractors, accountants, and mid-level managers. That model is collapsing. The rise of remote work and the decline of the 9-to-5 commuter culture have left many of these office campuses half-empty.

In response, Montgomery and Frederick planners have launched a rezoning blitz. The Lakeforest Mall site in Gaithersburg is slated for reinvention as a dense, walkable “town center,” while Germantown and Clarksburg are encouraging biotech campuses that combine laboratories with condos, restaurants, and coffee shops. Frederick has gone even further, designating “innovation districts” that blend housing with high-tech workspaces in what was once farmland.

Proponents call it the future—compact, transit-oriented communities where people can walk from their apartment to their biotech job to a brewery down the street. But to skeptics, it looks like an urbanization of suburbia: government planners using zoning code to force density where people once chose space.

The Rise of DNA Alley and the Cyber Corridor

For decades, I-270 has been nicknamed “DNA Alley,” thanks to its proximity to NIH and FDA. Rockville, Gaithersburg, and Germantown now host more than 300 life sciences companies, with giants like AstraZeneca and emerging startups drawing billions in investment.

Layered on top of this is a cybersecurity boom, fueled by proximity to NSA at Fort Meade and federal contracting dollars. Deloitte, Lockheed Martin, and a wave of startups are setting up labs and offices along the corridor, competing for the same pool of highly skilled workers.

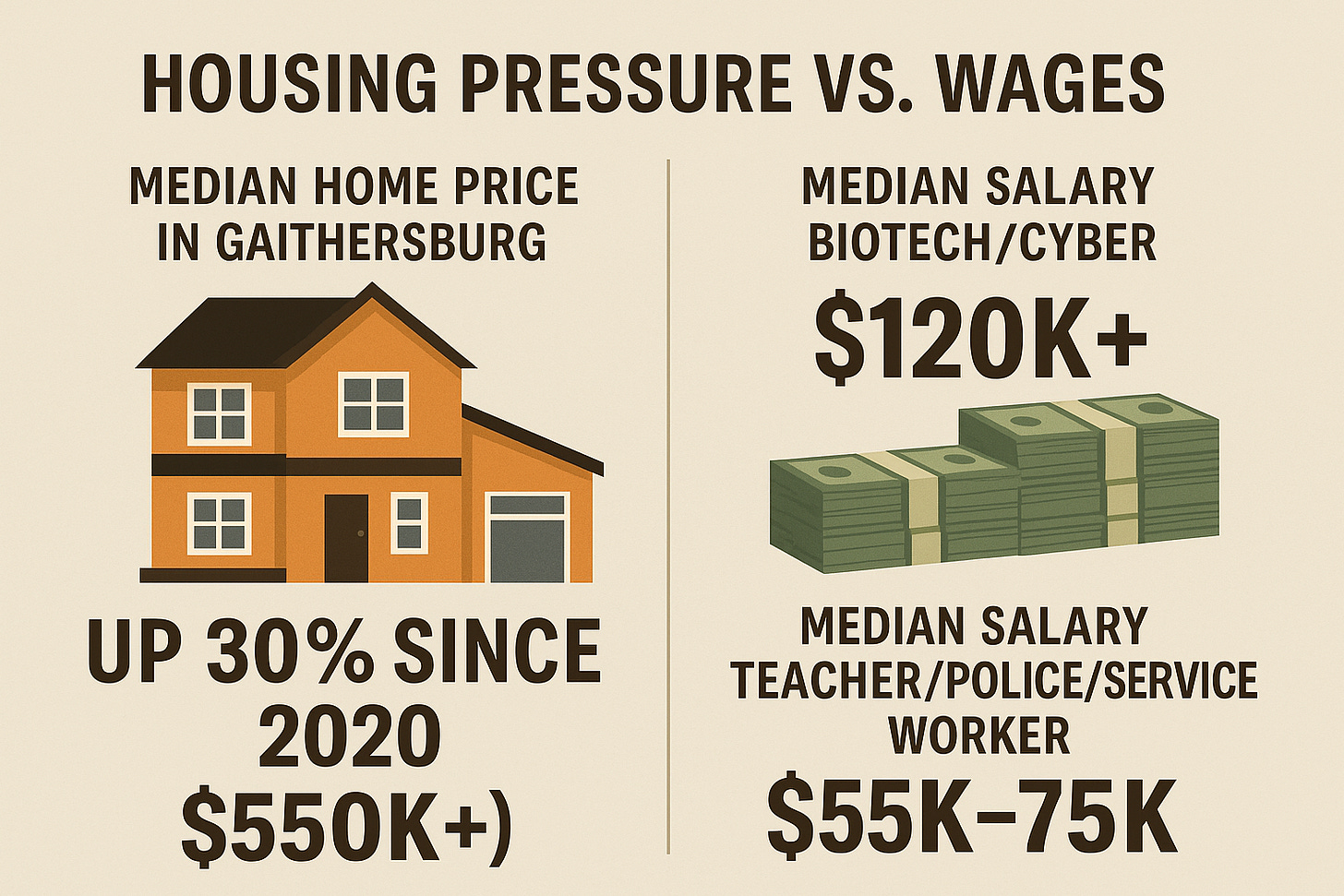

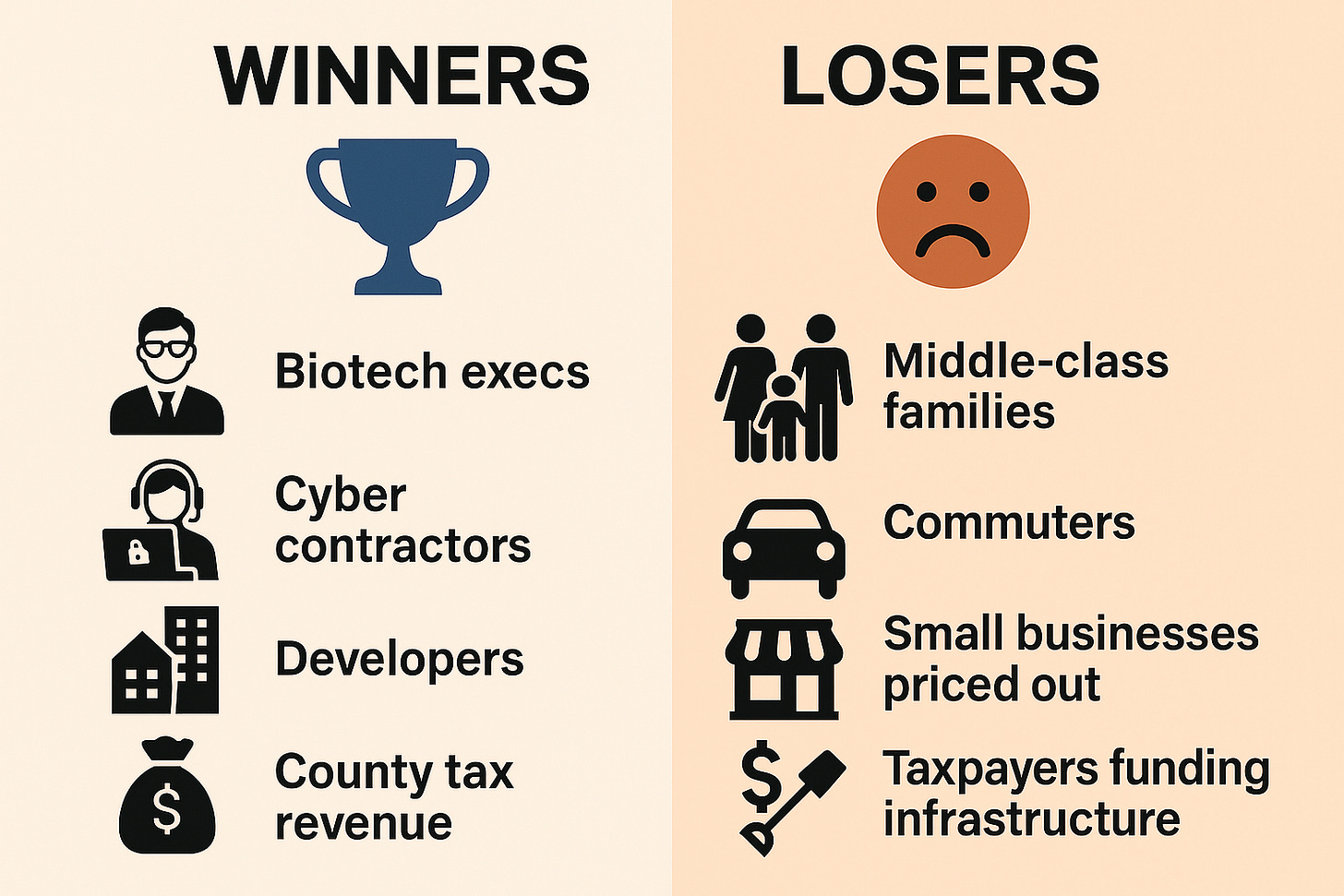

This is great news for those with PhDs in molecular biology or cybersecurity certifications—but it also hardens the economic divide. Jobs in these sectors average $120,000 or more, far outpacing local service jobs. That disparity means wealthier newcomers can bid up housing, while teachers, nurses, and blue-collar workers get priced out. The corridor is being remade for an elite workforce—one subsidized by federal contracts and state incentives—while ordinary families struggle to stay afloat.

Housing: The Affordability Crunch

The economic boom has a dark side: runaway housing costs. Gaithersburg’s median home price has jumped 25-30% since 2020, while Frederick’s once-affordable market is catching up fast. New townhomes in Urbana sell for $700,000 and up—hardly “starter homes.”

Local governments insist rezoning for mixed-use and multifamily apartments will solve the crisis. Montgomery County has promised 15,000 “affordable” units by 2030. But “affordable” is often defined as below 80% of area median income, which in Montgomery County is nearly $130,000. That means a firefighter or single parent making $60,000 still doesn’t qualify.

Meanwhile, farmland is being converted to subdivisions, eroding Frederick’s rural character. Residents complain that open space is disappearing, replaced by high-density housing that clogs two-lane roads and overwhelms schools. For many, the American dream of a backyard and affordable home is slipping away, sacrificed to the altar of “smart growth.”

Infrastructure Strain: Who Pays?

The I-270 corridor already handles 100,000+ vehicles a day, and congestion remains legendary. State planners hope bus rapid transit (BRT) and “smart traffic” systems will ease gridlock, but history suggests otherwise. Maryland taxpayers have watched billions wasted on transit schemes like the Purple Line, while roads continue to choke.

Upgrading water, sewer, and power systems for biotech campuses doesn’t come cheap. Estimates suggest local governments will need billions in new infrastructure investment over the next two decades. Supporters tout the tax revenue from high-tech firms, but history shows these projects rarely pay for themselves. Taxpayers, not corporations, usually foot the bill for expanded schools, fire stations, and widened roads.

Winners and Losers: A Tale of Two Counties

For Montgomery County politicians, the transformation is a victory lap: proof of progressive planning and economic leadership. For Frederick, it’s a double-edged sword. On one hand, biotech jobs bring prosperity. On the other, the county’s semi-rural identity is being erased by sprawl disguised as “innovation districts.”

Residents of Mount Airy and Urbana complain their quiet communities are being turned into commuter suburbs for Washington elites. Frederick County’s 2023 Comprehensive Plan promises to preserve farmland, yet rezoning continues to carve up open space. The question is not whether growth is coming—it’s whether the people who built these communities will still recognize them in twenty years.

The Political Dimension: Central Planning Disguised as Progress

From a conservative’s perspective, the quiet transformation of the I-270 corridor is less about organic growth and more about government engineering. Zoning codes, subsidies, and federal contracts are steering development into biotech and cyber, whether residents like it or not.

The MD 355/I-270 Technology Corridor Study, “Corridor Forward” transit plan, and county master plans all push the same vision: denser housing, walkable communities, and expensive transit. The question is whether taxpayers or voters ever truly signed up for this transformation.

The quiet part is that much of this happens out of public view—piecemeal rezonings, planning documents few residents read, and county council votes scheduled for summer afternoons. The result is a sweeping transformation made without broad consent.

What Comes Next?

By 2040, projections suggest the I-270 corridor could add 50,000 jobs and $10 billion to regional GDP. Lab vacancy rates are under 5%, and biotech firms are scrambling for space. Frederick and Gaithersburg are already national players in life sciences.

But at what cost? Families priced out of their neighborhoods. Traffic congestion that only worsens. Taxpayers left holding the bag for infrastructure. And a regional identity shifting from middle-class suburbia to elite corporate enclave.

For those who benefit—biotech executives, cybersecurity engineers, developers—it’s a golden age. For the working families who once fled D.C. for affordable homes and good schools in Montgomery and Frederick, it’s a slow-motion squeeze.

Conclusion: A Cautionary Transformation

The I-270 corridor’s transformation is real, powerful, and largely invisible to the average commuter stuck in traffic. It reflects both the dynamism of Maryland’s economy and the heavy hand of government in shaping growth.

The winners are clear: multinational biotech firms, cyber contractors, developers, and local governments chasing tax revenue. The losers are just as clear: middle-class families facing soaring housing costs, taxpayers burdened with infrastructure bills, and communities losing their suburban or rural character.

Marylanders should pay attention. Because while the Purple Line grabs headlines, the future of Montgomery and Frederick counties is being decided quietly, in rezoning hearings and planning studies. And by the time most people notice, the transformation may be irreversible.